Hi, I’m Charl. And I work for Love and Money. You probably haven’t heard of me or my agency. Neither have many of your clients. And for me that’s the problem.

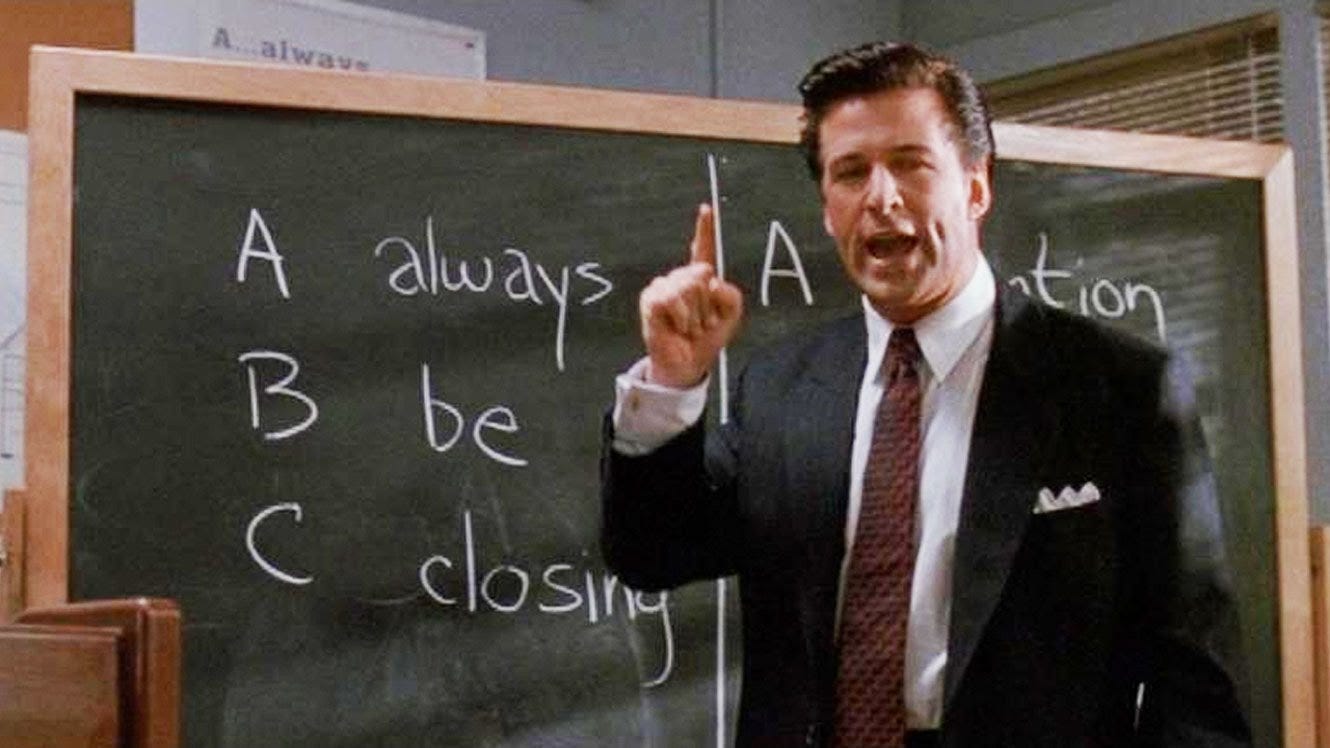

Thankfully, it’s not a unique problem — it’s the same problem every business in every industry encounters when they’re not all that big. Which means that there’s a pretty good playbook out there for what to do in this sort of situation:

Invest in brand, advertising, and sales.

This is an industry built on Customer Acquisition Costs and ROI

Luckily for me, brand and advertising is exactly what I've been doing for the last 20 odd years.

I know the pitch well, because our whole industry is essentially built on it:

Invest an amount of money or effort to capture attention and good will

Convert some percentage of that attention and good will into sales

Banks do it. Car companies do it. Frank Walker from National Tiles does it.

Sales wasn’t what I thought I’d get into as a young design graduate. But a focus on ecommerce over the last 10 has forced me to think pretty hard about how the brand and advertising decisions I convince clients to make actually cash out, and their ad spend convert into actual revenue. But again here there are a bunch of tactics that have a great track record. Big buy buttons. AOV-driving upsells. Funnels that convert one-time sales into life time customers. All of them, though, work with the basic quirks of human psychology to make it easier to buy.

All of these investments are made with one piece of math in mind: pay money in the hope of securing a life-time valuation out of a client that will be profitable. Invest now, get ROI later.

It’s this work — investment in brand, advertising and ecommerce platforms — that keeps a lot of us in business. And yet, for all of our selling of this basic premise (and this underlying promise) we seem to be particularly averse to engaging in this sort of practice ourselves.

We’re the only industry unwilling to pay it ourselves.

Every business we’ve worked with thinks about their Customer Acquisition Cost. We can too. We’d recommend a client think about their ROAS. We need to think about ours.

Let’s say I have a makeup business, and a customer buys at an Average Order Value (AOV) of $90. Let’s say it costs me $30 to make the product, and a further $15 to ship it from the factory to the warehouse to the customer. I have $45 in Gross Profit left over. That means I can spend up to, say $30 on paid ads to aquire that customer (CAC) and still have profit left over. And while that’s not an incredible GP:CAC ratio, what’s interesting is if that customer buys again and again — I’ve spent that initial $30 to acquire them, but each time I need to retarget them, I can spend less, because they already know my brand is cool and my product is good.

This is dead standard stuff in the world of ecommerce, SaaS, and almost every industry on the planet. And it’s exactly the same in our industry.

If I make $100,000 from a client in a given year, and I have a gross margin of 66%, then how much should I be willing to pay to acquire that client? What if the client’s worth $500,000? Or more?

Finding this number is as critical to my business as it is to any of my clients. And it doesn’t matter how good things are going right now, as my old CEO at Interbrand once said to me “any agency is only 6 months away from shutting its doors.” So if I’m not re-investing today’s capital back into finding tomorrow’s clients, I’m very possibly fucked. And if I’m not making enough profit on a job to be able to invest in acquiring new business, or I’m burning my team out trying to keep my own lights on, then I have a bigger problem to solve.

In short, if I can’t afford to pitch, I’m already paying for it.

Invert! Always Invert!

In my last post I tried to create a steelman argument from the one neatly articulated on www.nofreepitches.com by adding a few other points I’ve seen made on Design Twitter, industry rags and LinkedIn over the past few years. Then, in the interest of creating a healthy debate, I suggested we consider do as the great mathematician Jacobi always advised, and invert the thinking.

The counter-argument, then, is:

Pitching is more about what you know than who you know.

Pitching is a sign of a competitive market, and competition forces innovation.

Pitching an idea is not executing an idea, and an idea is only as valuable as its execution.

Pitching is not the reason our teams’ mental health suffers. But it is a good excuse.

Pitching makes meaningful work possible if we make time for it.

Pitching is an example of what we could do with more time (if that’s how we pitch it.)

Pitching for new business is a critical investment for (sm)all studios.

Pitching exposes how broken our business model is.

Pitching teaches us what clients value about our work. Let’s improve our pitch.

Pitching relies on knowing the true value of our product.

I covered the first 4 points in my prior post, “We Can’t Afford to Not Pitch”. Next, I want to give a more optimistic spin by offering some tools and ideas that I’ve seen work in other industries, work for my other businesses, and work for my agency, too.

“For some odd reason, I had an early and extreme multidisciplinary cast of mind. I couldn’t stand reaching for a small idea in my own discipline when there was a big idea right over the fence in somebody else’s discipline.”

— Charlie Munger

5. Pitching makes meaningful work possible if we make time for it.

“Pitching mandates unreasonable deadlines that impede meaningful work.”

Every business should be invested in where its next clients are coming from. That means investing in brand, advertising, and sales.

It’s only recently that we’ve had a whole department dedicated to sales and customer retention. That’s normal; in a small team there’s often a few people wearing a lot of hats. So instead we used a percentage of our team’s time on pitching for new business. It’s exactly the same thing as hiring a dedicated department, just part-time.

Properly considering Cost of Acquisition simply means building this into a budget. And correctly accounting for that cost not at the full rack rate (what you’d charge a client for your employee’s time) but at the cost to the business.

As for the deadlines, if you’ve budgeted time to pitch and you’re still not meeting your deadline, you need to consider exactly what your client has asked for, and mitigate expectations accordingly.

6. Pitching is as resource intensive as we choose to make it. We need to be clear on the brief.

“Pitching is extremely time and resource intensive.”

This almost certainly seems to be true. I remember working on crazy pitches at Interbrand, DDB, TBWA, and Taboo. We've done a few ourselves at Love and Money. But who's asking us to do this?

Our industry has an uncomfortable history of conflating egos with client requests. And while we can be absolutely sure that some (awful) clients are explicitly using the pitching process to see how high they can make an agency jump (or how free they can get something), I'd suggest that the vast majority of clients simply want to better understand who they're getting into bed with before they agree to spending somewhere between $20,000 and $2,000,000.

So, rather than throwing everything we have at every single creative pitch, can we not be more creative? In researching this article, I came across the following, I won’t name the source:

“Clients who are incapable of preparing an adequate design brief often use competitive design submissions to assist them in defining the particular project requirements, and to help them gain an understanding of the design process and in order to determine cost.”

But who better than us, a creative partner who writes design briefs all the time, to help them refine that brief? Do we walk into doctor’s studios briefing them properly? Or drive up to a mechanic’s and diagnose the problem for them? Nobody wants to buy a dog and have to bark themselves.

We see this pitching process as an opportunity to show value by helping clients to understand the road ahead. To repeat back to them what we heard in a process modelled on The Feynman Technique to show that we’re listening, and to lower the expectations that we’ll have all the answers straight away.

As Richard himself used to say…

Usually, our clients love the opportunity to talk about themselves and their problems (that’s not a client thing, that’s a human thing.) Listening is a great way to start a relationship. We all know this; how many times have you read “It all starts with a conversation” on the “Our Process” page of another design studio?

7. Pitching is an example of what we could do with more time (if that’s how we pitch it.)

“Pitching isn't a reflection of what we can do with more time and deeper thought, and is in fact anathema to it.”

Pitches don't give a good idea of what we're capable of with more time and more budget. But they should be.

We test drive cars. Try on swimsuits in change rooms. And every single piece of software we download either kicks us out after 30 days or serves us ads tirelessly. Or sells our data to 3rd parties for yet more advertising.

All of these experiences are designed to give the minimum viable quantum of the full experience needed to convince the client to buy. You don't test drive your new BMW on the Autobahn. You don't go swimming in your new bikini. But you get an idea of what it might be like if you did.

It’s very likely true that your creative team will come up with something better if they have more time and budget — nine times out of ten, anyway. But can this not be adequately handled with appropriate caveats and intelligent expectation-setting? And are we absolutely sure it needs to be? If a client is willing to pay you thousands (or millions) of dollars for your time and materials over the coming 3—12 months, surely they understand that they're not going to get the whole horse and cart in a couple of weeks.

I often think about how an ice cream shop will let you try 5 different flavours before committing your whole $7 to one. And we expect clients to pick us, untested, off a website that literally says the same as every other agency. Even open homes give us half an hour to poke around before asking for your money.”

In fact, we see this as an opportunity. This is how we counter-position our pitching process against that of other agencies. We use this process to de-risk our downside and offer a potential win-win to both us and our clients.

Free Pitch SOP

State that our usual process take 12 or 24 or 52 weeks or whatever, and includes however many workshops and sprints and rounds of amends. We have a way of working, and it works for us.

Explain that we’d usually take this time to understand our client’s business fully, and that if we don’t, we’ll be more likely to miss the mark.

Then explain that the idea that we’ve come up with in order to respond to this pitch has had about 1/10th or 1/100th or whatever of the thinking we’d usually put in, and that it would be bonkers to expect anything else, given the time constraints.

So therefore, what the client is looking at is not the finished product.

Then offer the client the full quote for the finished product, which they can of course accept or negotiate as they wish.

Then admit that sometimes magic happens, and that our team has worked hard and does like the work that’s been done (we’d not present it otherwise.) So if the client wants to go ahead with the idea already presented, they can purchase it at the commensurately reduced cost. Any further amends etc will be scoped separately.

Then send the client that quote, too.

So, they can buy our agency’s time at the original cost, or close to it, or the idea in front of them for some reduced cost, or close to it. Either way, we get paid for the time we spent, and our client can re-allocate that budget to more work with us, or doing some other thing that they also need to do.

8. Pitching for new business is a critical investment for (sm)all studios.

Pitching creates untenable economics that only the big studios can afford.

OK finally, some maths. Everyone’s favourite.

COA (Cost of Acquisition) or CAC (Customer Acquisition Cost) or CPA (Cost per Acquisition) is a critical part of any business. It's so important it has at least three acronyms.

Every good business owner I've ever worked with does some sort of calculation of their Customer Acquisition Cost. Oddly, we’re an industry that thinks it never needs to pay it.

Here’s some math I found in an AGDA article on “ditching the pitch.”

If a designer were to consistently engage in free pitches and win say, one in every two, they would have to be building in extraordinary margins into the projects they did win just in order to survive, let alone make money!

And it’s bad math. For three reasons.

Firstly, because your cost of acquiring a customer will always come out of your gross margin, whether you think to account for it or not. Secondly, because our gross margins are notoriously high (industry standard is to charge 3x what you pay an employee out to a client). Thirdly, because if any business in any industry won 50% of the business it pitched for it’d be rightfully elated; those are great odds. (Equally, any business that can’t make money with that sort of win-rate needs to look elsewhere for its problems.)

The article goes on to talk about how much harder this is for small businesses, for whom“$50,000 is a ‘big’ job.” But those costs also scale; if you’re a small studio, you don’t have to pay a big team to work on a pitch, because you don’t have a big team.

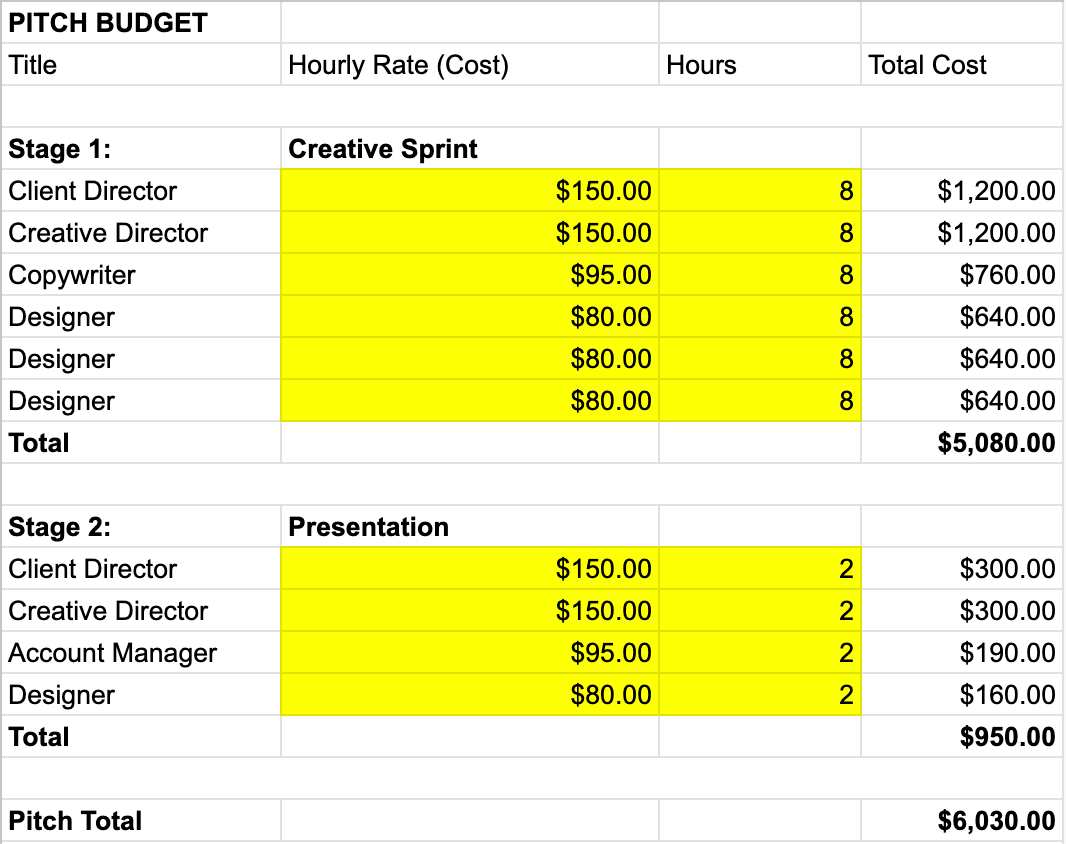

The reality is this: if you make the industry standard 66% gross profit on a given job, and you win 50% of your free pitches, you have just over $4,000 in hard cost (salary) that you can spend on every pitch. That’s a week of a designer that you’re paying $80 per hour, and just about a day of a creative director.

Pitch Calculator

In order to understand how it works, we simply need to understand that every time we pitch we have a probability of winning the pitch based on our prior record. We can go into probability theory and expected value and whatnot, but there’s no real need.

To figure out how to make money on pitching for “free”, all we need are the following numbers:

Average Deal Size: This is the typical revenue expected from each successful client project. We find this by getting the revenue from all of our clients over a period of time (say this financial year) and dividing that revenue by the amount of clients we have.

Average Gross Margin: How much money we have once we’ve paid our team to deliver the work. We try to focus on the variable costs that scale with each job, not the hard costs that we have to pay whether we win this client or not. For this reason, the majority of our team's time should be included here, but the computers they work on (or the studio they work from) should not. This is expressed as a percentage.

Average Gross Profit: This is the Average Gross Margin times our Average Deal Size, expressed as a dollar figure.

Cost of Acquisition as a Percentage of Gross Profit (CAC:GP): This figure represents the portion of the gross profit that we’re willing to reinvest in acquiring new deals. In most industries a CAC:GP ratio of 3:1 is pretty damn good. Let's be conservative and call it 4:1 to include a Margin of Safety.

Cost of Acquisition Budget (CoA): We take the Gross Margin average deal and multiply it by both the win rate and the CAC:GP.

Win Rate: We find this by totalling the number of pitches we’ve won and dividing it by the number of pitches we’ve done over a given period of time. So if we pitched twice and won once (as in the incredible example above) your number would be 1/2 = 50%. But that's nuts, so we go with something more conservative.

Budget per Pitch: Finally, we multiply the total pitch budget by your win rate to get the amount you can spend on any given pitch. But remember, this is not to be calculated as opportunity cost, but rather the hard cost to your business.

Below is an illustrative example. And if you want to try it yourself, a Google Sheet you can copy and put your own numbers into.

Free Pitching isn’t Free

There’s no such thing as a free lunch. Especially not when the client is paying. But with some basic probabilistic thinking we can make pitching pay for itself.

Next, I want to tackle why I think this groupthink is dangerous to an industry I’m passionate about, and which conversations I think will lead to healthier outcomes for all of us.

Subscribe below to make you geddit.