Engaging in digital dialogue means listening as well as talking. But social media doesn't exactly reward thoughtful silence. And COVID makes it harder to engage anywhere else. What are brands and consumers meant to do?

The world’s been a weird place lately. Have you noticed? Everyone else definitely has. And social media’s encouraging everyone to share their opinions — loudly. And, as ever, what’s true for brands is true for consumers.

A couple of recent articles from Slow Boring and I—D have got us thinking about what that’s doing to our thinking. And given our work largely about creating dialogue online, and our process is all about getting less-wrong, we thought we’d raise some concerns, talk about the dangers, make some suggestions, and provide some resources we’ve found helpful.

2021 Has Been No Less Weird Than 2020.

It’s been a trying ~18 months, to say the least. While our team is spread out across 6 cities across 3 countries, most of us are in Melbourne or Sydney, which means a lot of us are currently in lockdown — some of us for the 6th time. And while we’ve been extremely lucky by most standards, we’re still at home, often bored as shit, or dealing with small children (or getting ready for them) and generally deprived of contact with the outside world.

We’ve all got very little to do.

So, like many others, this leads us back to our screens. We flick through news. Read Twitter. Doomscroll Instagram — you know the drill. We’re inundated with roughly 7 billion problems and issues and causes and injustices. And it’s not exactly bringing out the Better Angles of Our Nature.

“Just Asking Questions.”

A combination of boredom, uncertainty and solipsism is leading us to engage in the Real World™ primarily through online channels. The Digital Fairy suggests that we’ve flattened our online and offline selves entirely:

After 2020, the (always somewhat false!) division between [our] online and offline selves has completely collapsed. The idea that you could think something or do something and not post about it is alien. “As a result, I believe we have reached our point of singularity with the internet: the significance of online action has surpassed its physical equivalent, posting is now the primary activity against which everything else comes second place.”

— Olivia Yallop

You’ll have noticed more people have more opinions about more stuff, more often, utterly irrespective of how much they should know about something. Like influencers questioning how safe vaccines are. Restauranteurs wondering aloud whether masks are an effective defence against airborne pathogens. High school students debating whether police forces in far-off lands should have their budgets cut. Bankers suggesting how to resolve a generations-long conflict between Israel and Palestine. Actors showing governments how to solve global warming. Tinder hopefuls explaining why capitalism doesn’t work and how to move past it. And every PT solving the twin epidemiological/economic puzzle of whether or not we should be in lockdown.

Every single person, it seems, needs to comment on every single thing, every moment of every day. Even if it’s “just asking questions”.

Social media, under the guise of like, connecting people or whatever, is incentivising this behaviour. It makes you feel good about participating, and doesn’t punish you for not understanding or engaging. In the Attention Economy, it’s about quantity, not quality.

It’s making us feel like we’re doing something good. But since when has feeling good and doing good been the same thing?

Why is Nobody Talking About This (Anymore)?

As Matt Yglesias suggests, this combo of too much input and not enough output is exacerbating our innate desire to see ourselves as important and relevant in the general story of the human race, leading us to catastrophise about how totally fucked we are in basically every way.

This ID article asks When everyone is an activist online, is anyone? Which broadly gets at the same problem. It tracks how we’ve all jumped on to an array of Urgent Causes from our couches because it costs us very little to do so and because it makes us feel like good people. Even if only for a fleeting moment.

Critically, both articles arrive at the same point: this kind of “contribution” to the public discourse is at best facile, and more likely just straight-up counterproductive. It seems we dedicate too much time and attention to making mountains of molehills and articulating massive, pressing, world-ending issues, and then move on before we’ve even nearly done doing the actual work required to work them out. 🤙🏽

This is a Problem for You and Your Brand, Too.

Brands are anything but immune from jumping on the alarmism/opinions/solidarity bandwagon. Digital (read: social) media has made it easy for brands to “be part of the conversation” in ways that typically range from whatever glib to unhelpful to bullshit.

Brands, people and politicians alike have been boycotted, cancelled, cut off or de-platformed for everything from retrograde ideas and practices, deceptive PR, harmless missteps, genuinely abhorrent behaviour, generally not getting with the program, and everything in between.

This is, in some cases, a very good thing. We need to move forward; that’s what a liberal society is all about, and what being “progressive” means. Literally. Progress.

But while Cancel Culture (and its next iteration, Consequence Culture) has been appropriately critiqued for being too quick to punish ideas, celebrities, and companies for not “reading the room", or keeping up with the rapid rate of cultural change, it’s the delta between what’s said and what’s done that’s the real rat that everyone’s (meant to be) sniffing out. Like when you run global ad campaigns and PR statements that stand in solidarity with the BLM movement/moment and then someone Googles your board and wonders aloud why things don’t look so… diverse.

The fact that this is a bit of a cheap shot — there’s almost certainly a difference between protesting systemic racism and police brutality, or championing Colin Kaepernick, and taking affirmative action on your board — or that Nike or Apple helping to normalise progressive talking points is surely a net gain, culturally speaking, is kind of the point. Social media’s given everyone the opportunity to point fingers and criticise almost anybody for almost everything. And because it incentivises quantity (reach and volume of posts) over quality or veracity (remember how stupid “alternative facts” sounded in 2016? Turns out the future is post-truth) you can more or less kiss your nuanced arguments goodbye, along with your brownie points for giving it a go.

As hard as it is to keep up with What’s Important Right Now, and as unpredictable as consumer sentiment can be, the most sure-fire way for an organisation to get itself cancelled on the internet is when the brand is promising something the product isn’t delivering. Whether that’s pretending to care about something it obviously doesn’t, or pretending to know about something it obviously doesn’t.

The Dunning-Kruger Effect.

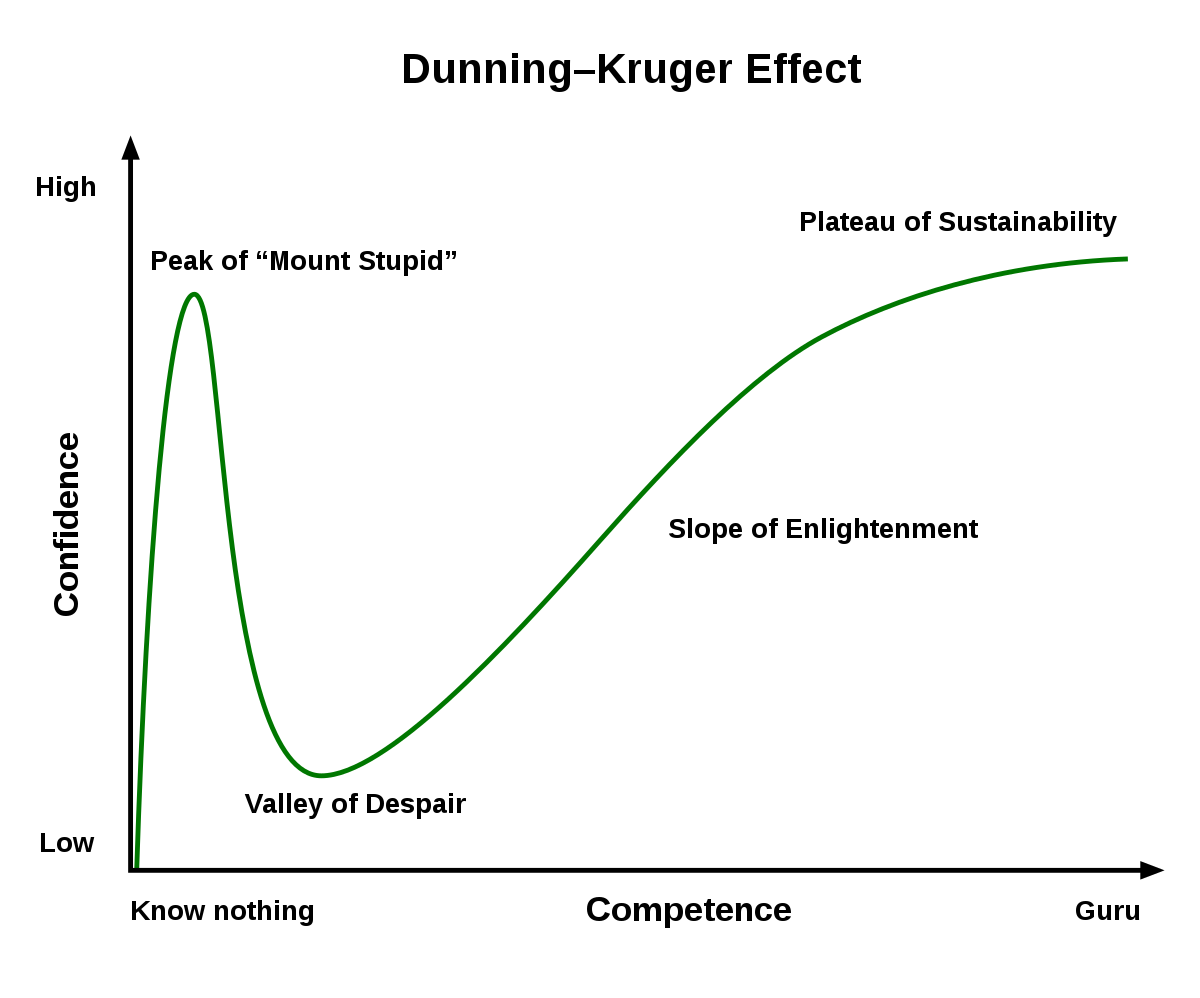

This isn’t the first time humanity’s been called on its bullshit. Our tendency to overestimate our importance in the Long Arc of History is matched by our tendency to overestimate how much we know and how good we are at stuff. It’s even got a name: the Dunning Kruger Effect. The diagram, in fact, is perhaps our favourite of all graphs. “Peak of Mount Stupid” is Big 2021 Energy.

In the interest of humility and word count, rather than us explaining it, here’s a TED video from David Dunning, 50% of the effect’s namesake:

Point is, whether we like it or not, we don’t know anywhere near as much as we like to think we do. And pontificating on shit we don’t understand can go from being embarrassingly naive to extremely dangerous. Like remember that time when ~30% of the western world all of a sudden just decided it knew more about immunology and how safe vaccines are than the people who have spent their lifetimes literally diagnosing and treating diseases and it caused hundreds of thousands of unnecessary deaths? Arnie does.

So, we’ve got an Internet full of people loudly, angrily, self-righteously, dangerously knowing-it-all, and it’s almost certainly not a good thing. So what do we do?

How to Reckon Without the Reckoning

As people or brands who care about stuff, and also care about what others think about what we think about stuff, how do we participate without making things worse? How do we ensure we raise necessary points, ask questions, challenge orthodoxy, and move forward? How do we contribute Important Thoughts to Necessary Dialogues, rather than just mashing our keyboards with our heads? Here’s what we reckon might help:

1. Don’t Tell Me You Value What You’re Not Willing to Pay For.

In a competitive market, people don’t buy products, they buy brands. The product is just the receipt. But while consumers are more than happy to pay a premium for a given leather handbag over the other and convince themselves that they’ve made a worthwhile investment, the fact is that this only works if the illusion is maintained. Meaning that if the product doesn’t deliver what the brand has promised to some acceptable degree your audience is going to take it as their divine right to complain about how you’ve ruined their life, and will think it’s only fair if they, in doing so, ruin your business.

Which is why it’s important to be selective about what you choose to invest in. Brands tell us what we should value — internally and externally — so we know where to invest our time, energy, attention and money. All of which is to say, if you’re going to go around saying you value something — you support a cause, say — you better make sure it’s something you’re willing to invest time, energy, attention and money in. It should impact the way you do business, make products, build your culture. It should affect your bottom line.

“A value isn’t a value until it costs you something.”

— ‘Bad Boy’ Billy Bernbach

So go deep rather than broad. Pick a few things you care actually care about, and invest accordingly. As a rule of thumb, you should be trying to start conversations that engage your audience to ask more. You should be both knowledgeable and proud of your commitments. If you’re saying stuff and hoping nobody looks too closely or hits you back in the comments, it may be a sign you’re backing the wrong ethical hobby horse.

2. Beta today. Better tomorrow.

Our Always Beta philosophy isn’t just a cute catch phrase. It’s the result of years and years of failure through hubris. We’ve learned the hard way that thinking you’re the Smartest People In The Room means that at best you’re not listening or learning, and at worst you’re a fool.

"When arguing with a fool, first make sure that the other person isn't doing the same thing"

— Old Proverb

We’ve learned that what’s true for us at a professional level is true for brands at the level of markets. Thinking you know everything before you open your mouth(piece) limits your chances for proper engagement and connection with an audience, and almost totally kills any opportunity for dialogue and feedback. It also makes you less agile, less resilient to change. Because we underestimate the value of what we don’t know and overvalue what we do know, we fundamentally misunderstand the likelihood of surprises, and miss opportunities, new ideas, and outside perspectives.

It is our knowledge — the things we are sure of — that makes the world go wrong and keeps us from seeing and learning.”

— Lincoln Steffen

So be prepared to be wrong, to learn, to change and update your views, and to be honest enough about your failures.

3. Be rational. And if you can’t, at least be humble.

We’re famously irrational creatures. Danny Kahneman’s work on Behavioural Economics has inspired a whole cottage industry of podcasts, books and blogs like Hidden Brain and Freakonomics that document just how totally irrational we are all the time. It’s fascinating. It’s literally human nature.

There are heaps of tools to help us to work with our cognitive biases — or to control for them if we can’t actually control them. fs.blog (part of Shane Parrish’s Knowledge Project) is a great deep dive into some mental models. There are great books like Scout Mindset and Thinking In Bets that give clear steps more rational thought. Patrick Collison is a great example of a modern Fallibilist in the Popperian tradition. Great work has been done by the likes of James Clear and Judson Brewer to help us create better habits of mind. And of course there are a million mindfulness apps and practices out there to bring us face to face with our own heads — we’d recommend Waking Up for a more science-y take on it all.

But while this is all the work of a lifetime, we can start with an attitude: humility. We know so much less than we think we do, and the best of us are those who not only admit this, but embrace it. Use it as an opportunity to learn and grow. As David Deutsch says, we’re only ever at the Beginning of Infinity. Human knowledge will always have further to go than it has already travelled. We could, and should, embrace this, revel in it. As Popper said, we should be so lucky to have problems; it gives us something to fall in love with.

Besides, it gives us creative types something to do.

“An unproblematic state is a state without creative thought. Its other name is death.”

— David Deutsch

Some Resources

Being a bunch of humans, we’re just as susceptible as everyone else to know-it-all-sim. Which is why we’re always building The Love + Money Anti-Library: a list of books, articles and podcasts that remind us how little we know. We’re updating it as we go, and there are plenty still to add.

→ Find that here📚.

Perhaps the weirdest moment came when all of Social Media decided in a matter of hours to block the sitting president of the most powerful country in the world. This was an unambiguously good move, and those publicly traded companies are well within their rights to allow or disallow whomever they want on their platforms, btw. If someone’s telling you it’s a free speech/first amendment violation, they don’t understand the concept and literally don’t understand the law. But still, it was pretty fucking weird.

Library link is private FYI! 🙏